Mike Kelley 1954 – 2012

This is not an obituary, or a critical reading of Mike Kelley’s work, but a more personal acknowledgement of what one of his lesser known works meant to me at a particular moment. It uses some of the same words and phrases as an obituary might, but thankfully I couldn’t get it to behave, so…

The first day of school, Autumn 1985. A dormitory town just outside Belfast. A base mood somewhere between the touchy-feely aftermath of Live Aid and the schizophrenic normality of a domestic civil war whose reality we kids weren’t meant to acknowledge. That morning the history text books were being handed out for the year and it seemed everyone but me was grabbing for the newest ones. I wanted one in condition D though (the lowest, most damaged, condition still deemed worthy of the description ‘book’), and I got lucky – receiving a ragged bundle of pages whose authoritative accounts of great events creaked under an impossibly vital biroed graffiti layer of absurdity, droll commentary and scatology. As the class were being given instructions on how to wrap the book in wallpaper to preserve its condition for the year (a rich joke in itself), I was barely listening – instead flicking through this gloriously dumb/smart portfolio of offhand insolence and marvelling at the fact that the voice speaking through these alterations seemed to have no echo in the voices I heard around me and yet somehow seemed much more recognizable and trustworthy than any of them were.

Seven years later I saw Mike Kelley’s “Reconstructed History” as part of his show at the ICA in London and had a shock of recognition – not so much of the form (though it was, indeed, a heavily –’childishly’– vandalized set of historical prints), but of the voice. Shot through this work and the rest of the show and catalogue was this perfect, brittle voice of defiance. It was a voice that flipped the authority of its targets with a hilarious economy of effort, where earnest cross-hatches were countered with quick strokes and crude phrases – though never more than enough. It was very funny of course, though along with the rest of the work in the show it made me think of the title of the then current Alice Donut album – “Revenge fantasies of the impotent”. There was a deeper melancholy there. “Decay is inevitable,” suggested the work – “Spare us the ‘nobility’ bullshit in the meantime…”

I took a lot of consolation from my recognition of Kelley’s voice as a young artist. It helped bridge the gaps between personal experience, punk, art history, pre-internet fanzine culture, critical/psychological/political theory, INFLUENCES, in a way that felt navigable. I gravitated towards other voices that reminded me of that voice – the irreverence of London collective Bank, the vernacular media poetics of Forced Entertainment, my own collaborators in the index co-operative (particularly Nick Crowe) and Kelley’s own contemporaries John Miller and Paul McCarthy – though you’d never necessarily guess all this, to look at most of my work then and since.

Certainly as time went on, I found that the connection with Kelley’s delinquent voice seemed less vivid for me, though the deadpan tautology of works like “An Actor Portrays Boredom and Exhibits His Knick Knack Collection” still resonates with me as one of my favourite know-it-when-I-see-it artistic tactics. I’d also say that, like the British poet laureate of moral disgust, Chris Morris, Kelley is still someone whose 80s and 90s work stands as a litmus test for whether you and I could ever truly be friends. And when I began working with spam e-mails, the most ubiquitous and despised data form of the globalization moment, it was with an indirect debt to Kelley’s treatment of the abject.

Mike Kelley made some extraordinary work, was a thinker of uncredited subtlety and sensitivity, and for better or worse, was a key figure in the reductive concept of “West Coast bad boy” mythology – a label that ultimately did him few favors. At his best he distilled work from the psyche of an infantile American culture and did so with an irreverence and unlikely morality that was easy to miss, what with it rarely being there in the nihilistic posturing of many of those who followed him, or way too heavily present in more heavy-handed political art (the practitioners of which tended to regard Kelley with suspicion, if not distaste).

At the very least, for that first sign from the culture at large that giggling in the dark might have its place, I owe Mike Kelley a debt. And when I heard the news of his premature death a couple of days ago, I wanted to stop for a moment and at least pay my respects, if not that debt. So this short note is a version of bowing my head in my best suit, muttering trite truisms, and looking suitably pensive and sad – with a giant cock and balls chalked on my back and homemade ectoplasm oozing down to fill my shoes…

Sócrates

I don’t write about football a lot on this blog, though following it is a big part of my life. But I wanted to write something to mark the premature death of Brazilian footballer Sócrates, whose ‘work’ was as influential on me in its time as that of any artist I’ve come across since. A version of this piece will also be the first post on a new blog on art and sport (mainly the latter) called Kid Weil (you can follow the Twitter feed @KidWeil here ). But for reasons that I hope will become obvious in the text I think it has a place on this blog too.

Brazilian footballer Sócrates Brasileiro Sampaio de Souza Vieira de Oliveira died today, aged 57. He was better known as Sócrates, or sometimes, ‘The Doctor’.

29 years ago, the team he captained changed my life.

In 1982 I watched the World Cup in Spain on TV – perhaps the first major soccer tournament where I was old enough to really follow the teams and have a sense that perhaps there were different ways to play this game. As a dutiful young student of the sport, I knew that I was supposed to admire Liverpool domestically and that the 1970 Brazil team of Pele et al were the greatest team ever, but if I was honest I was still repeating orthodoxies heard from others. I had yet to find a feeling for soccer that was my own.

Enter Brazil and Sócrates.

They played an attacking soccer that was perhaps the last true expression of an ideology of play that Brazil sides ever produced. Subsequent Brazil teams would be accompanied by exponentially ambitious ad campaigns featuring montages of Joga Bonito as practiced by the 1970 team and their supposed spiritual heirs, whilst their actual playing style devolved to more defence-minded pragmatism (arguably haunted by the ‘failure’ of the 1982 swashbucklers). The dourer they got, the more intense the media invocation of samba soccer became – a cynical and alienating marketing smokescreen. But at that moment, in the early days of the 1982 tournament, when Sócrates was waltzing around sprawling Scottish and Russian defenders and Zico and Falcao were nonchalantly lofting passes and shots into tiny windows of space no one else seemed to have noticed, this boy was transfixed by their movement, their cool and by the fact that they always believed in their ability to outscore the opposition (as Steve McClaren later said of the turn of the century Man United team, they were never beaten, they just ran out of time).

I wanted them to win. Actually, no, I wanted Northern Ireland to win and willed them through a torturous siege against Spain in that tournament with what I now recognize as the traditional religious agonies of the long term fan. But I wanted to keep watching Brazil – I wanted to see what they were going to do next. When they were surprisingly eliminated by Italy and a resurgent Paulo Rossi, it felt more traumatic than Northern Ireland’s eventual, inevitable defeat because it was like a line of thought being suppressed – a teacher’s command to settle down now.

Yet once you’d known it, it couldn’t be unknown. I kept watching the tournament – I remember Tardelli’s operatic bliss at scoring the winning goal in the final, I remember gasping at Harold Schumacher’s assault on Battiston in the France v Germany semi-final, but my abiding memory of that World Cup is a feeling, synaesthesic in its combination of color, film grain, audio compression and a sense of sustained anticipation. It’s a memory that starts not with goal highlights but with a transition: either the moment when Brazil would pick up the ball at the edge of their own area and suddenly their whole formation would transform into one of fluid potential, or a later moment when that wave is just about to break on shore – when an attacking midfielder (usually Sócrates himself) would be poised with the ball 30 yards out as players swarmed in front of him and across each others’ paths and I’d find myself leaning in to the TV waiting for his creative decision.

I didn’t know at the time that Sócrates said of soccer:

“To win is not the most important thing. Football is an art and should be showing creativity. If Vincent van Gogh and Edgar Degas had known when they were doing their work the level of recognition they were going to have, they would not have done them the same. You have to enjoy doing the art and not think, ‘Will I win?’ ”

I doubt I’d have been happier then if I had known he’d said that. Even now, I don’t need the appealing post-rationalising that might reference his life as a medical student, a polemicist, an advocate for Brazilian democracy, an admirer of Guevara, Castro and John Lennon – rich biographical texture though that might be. I knew then what I know now, that seeing him play was the moment I first trusted my own taste in the game. I didn’t need anybody to tell me that this was beautiful and the fact that Brazil didn’t win the cup was ultimately irrelevant. Because in those moments it felt like anything could happen and having happened once I thereafter had to believe such moments could happen again. I watch for them in soccer of course, perhaps more in hope than expectation, but I treasure them when they appear in other aspects of my life.

Recently I was in Zucotti Park on the night before Bloomberg’s first threatened eviction of Occupy Wall Street. A mass clean up was in progress, intended to thwart his claims that the protest needed to be broken up for reasons of public hygiene. The mood alternated between conviviality and tension at the thought of possible violence the next day. It had been raining intermittently but around midnight the skies suddenly opened and there was a palpable moment of uncertainty, as if everyone might scatter – a moment broken by a belly laugh that swept across the whole square and dissolved into cheers and chants of defiance.

I heard the news of Sócrates’ death this morning. And when I summoned that affective memory of his 1982 team in perpetual brimming potential I ended up thinking of that much more recent, absurd, fantastic moment in the park. This is not a facile equation of the two phenomena, but an admission that my own limited ability to appreciate the latter started not with my political education, but with a foundational moment of recognition granted to me by Sócrates’ particular generous genius. It was from his team that I first learned that no matter what the results on paper say, what happens next might be beautiful. Now more than ever, I am grateful for the lesson.

Art & Law show

I recently finished a residency with Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts with a great group of artists and writers, who met every couple of weeks with experts in the fields of Art and Law, to discuss issues relating to these fields and their points of intersection. The conversation ranged from practical issues regarding copyright and trademarking to more abstract discussion on the role of law in society. The conclusion of the residency is a show taking place at Sculpture Center, starting December 8th. I’ll be showing some ATM work and the single screen version of my recent film with Carl Hancock Rux, The Flitter (first showing in New York City). Hope to see some of you there.

We are Grammar

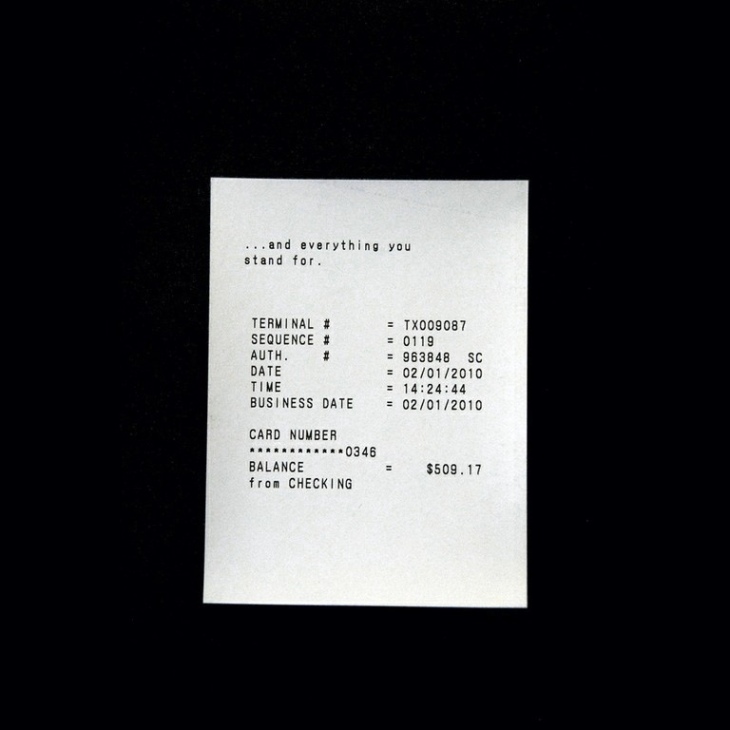

Some installation shots from ‘We are Grammar’, a show looking at a ‘third generation’ of visual artists working with language. Its run just finished. It was curated by Dave Beech and Paul O’Neill and ran at Pratt Manhattan Gallery. My contribution was the following receipt from a hacked ATM.

Landscape with Computer

This view from my studio window at EMPAC reminds me of a comment by a pensioner in Liverpool, during a Superflex project I was part of some years ago (working with residents of tower blocks in the city to produce their own web tv channel). The pensioner was a lifelong Marxist who was deeply saddened at the tower blocks imminent demolition as now “the churches will be the tallest buildings on the horizon again.”

This in turn makes me think of William Smith, the father of modern geological mapping, articulating the science of geology from the top of the tower of York Minster, as it was the only strategically placed manmade structure that was tall enough for him to confirm his theories about the processes of rock formation.

The desktop picture on my laptop has been a constant through my time at EMPAC. It’s Nicolas Poussin’s “Landscape with Diogenes”. It shows the moment Diogenes discarded his last possession – a piece of technology (supposedly he saw a youth drinking water with cupped hands and threw away his drinking cup, seeing he had no need for it).

And the tapes to the left of the laptop are part of the hundred hours or more of footage that were shot for The giSt n.

The EMPAC show is running till April 30th, but my personal time upstate finishes tomorrow. Just finishing up the principal photography work for a documentary on my work, provisionally entitled “Deface the Currency”…

…that and looking out of the window, with increasingly fragmented thoughts and free associations. The adrenalin I mentioned in an earlier post is pretty much gone now. Time to get back to Brooklyn.

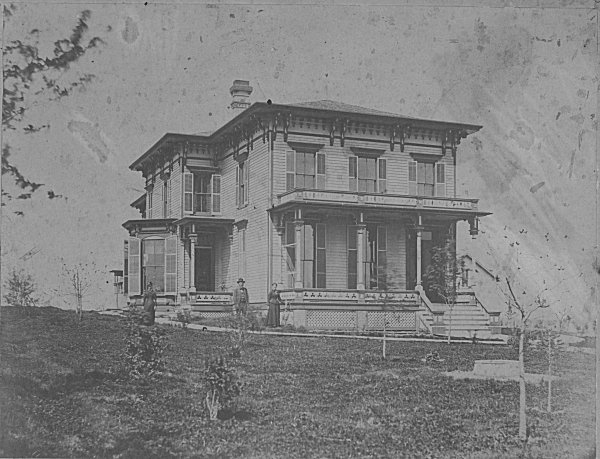

An easy mark

A rare image of the con artist Benjamin Marks outside his house in Council Bluffs Iowa. His gravestone is the starting point for ‘Spectres of Marks’, book 5 of my short collection Fair Use (notes from spam). Marks was an infamous exploiter of the patterns of human movement introduced by the nascent American railroad system and thus arguably a forerunner of some of the spammers and phishers of today.

Been thinking about him a lot whilst being in residence in Troy, working amongst the collection of pieces that make up my show/archive The Confidence Man at EMPAC. It’s an experience that came very hard on the heels of working in an intensely isolated way on the editing of The giSt n – which in some ways is a heavily filtered note to Marks sent via a contemporary group of actors, the cast and crew of The Sting, linguist David Maurer, and the numerous operatives of the late 19th and early 20th century big stores that were Marks’ legacy. I’ve been watching people respond to the film in the public spaces of EMPAC – watching them attend to it, ignore it, check their notes on it, etc. I’ve been meeting with individuals and classes over the last few weeks working in the space and we’ve been talking about the piece and how it relates to the rest of the work.

Normally if you finish a piece of work that’s for a particular show, you may work to deadline and finish it and then there’s this social event, an opening, where it becomes public and subject to all the contingencies that come with that. As much as it’s exciting to finish something and see people responding to it, it’s also a wrench to experience the transference from that intimate mode of working with the material. This tends to be compounded with the drop in adrenalin that’s there during production and installation periods.

At EMPAC though, there was no public opening and then I’ve been present and working in the space for the first few weeks of the show, so the wrench has been more subtle – more of a feeling of ebbing as I watch people come and go. There are two blackboards in the space for one of the other works in the show – they’re being updated with news of searches being called off or continued – the outdated news wiped off one of them with each status update. They’ve been making me think of each visit to the show as an act of erasure as well – a wearing away of my ‘ownership’ of the material as it becomes dispersed through the readings or neglect of other people.

Marks ran con games on Pacific Union rail cars, before extending the logic of his practice and opening the Dollar Store in Cheyenne. The Dollar Store had a window full of gaudy goods and a back room full of upturned barrels where 3 card monte was played. He would thus fleece travelers as they passed through town. He gave us the term ‘mark’ for victim.

Watching people interacting with my work, whilst I play the part of ‘visiting artist’, and watching its meaning and potential be shared, dispersed, disputed, I’ve been thinking of this image of Marks outside his house and of him in his dollar store – exploiting the potential of a fixed point on the network and yet in doing so consenting to the attrition of the traffic. Looking for marks. Making marks. Erasing Marks.

Been a while…

Haven’t posted for a while. Been taking some time to work on the two big video projects that grew out of Fair Use (notes from spam). Haven’t worked in video for a while either, and it’s been an intense period. My last post had me very excited at just having filmed Carl Hancock Rux for The Flitter. After working on a book project for a couple of years I’d very consciously sought to make the next tactical move be towards a collaborative form and I really enjoyed working with Carl and video artist Ben Tiven on this project and also working with Ben and several other very talented performers and technicians on the other major project, The giSt n.

Haven’t posted for a while. Been taking some time to work on the two big video projects that grew out of Fair Use (notes from spam). Haven’t worked in video for a while either, and it’s been an intense period. My last post had me very excited at just having filmed Carl Hancock Rux for The Flitter. After working on a book project for a couple of years I’d very consciously sought to make the next tactical move be towards a collaborative form and I really enjoyed working with Carl and video artist Ben Tiven on this project and also working with Ben and several other very talented performers and technicians on the other major project, The giSt n.

Both those films were produced at EMPAC, and there was definitely a moment coming back to New York on the train, where I could feel the weight of a 2TB hard drive filled with footage leaning against me in my bag – and an accompanying realization that the intensely discursive and enjoyable collaborative part was over and that this drive and the Final Cut interface were my companions for the coming months.

More on that process soon (maybe!), but for now it’s worth noting that both films are showing as part of my solo show at EMPAC, “The Confidence Man”, which runs until 30th April. I’m also working in the space most weekdays – editing a second screen cut for The giSt n and a mini-docuntary on the show and the work that inspired it. You can see versions of both pieces on the works section of my website, alongside a couple of other new ATM pieces, new newspaper and neon work, and the first piece I ever showed in America, Diogenes – which was in a show curated by Kathleen Forde – who also commissioned The giSt n and the current EMPAC show.

The image is a new piece of work that’s in the show – a hand-painted neon sign called “Social Capital”. It’s based on the bar code from Karl Marx’s “Capital Vol.1”.

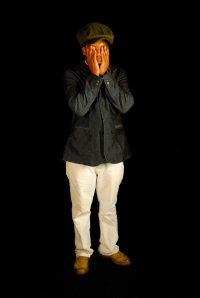

The Flitter

Had a great couple of days filming The Flitter with Carl Hancock Rux and Benjamin Tiven last week. Ben also worked with me on The Gist n in January and he’s a great camera operator/general technical supervisor as well as a very good artist in his own right. You can see his work here.

Had a great couple of days filming The Flitter with Carl Hancock Rux and Benjamin Tiven last week. Ben also worked with me on The Gist n in January and he’s a great camera operator/general technical supervisor as well as a very good artist in his own right. You can see his work here.

There are a lot of links to Carl on the web – I’d follow any and all of them. He’s an amazing writer/ performer/ musician and an extraordinarily generous talent. I was thrilled he agreed to work on The Flitter with me and he made some very difficult material his own. We’d planned to film in segments but he performed the entire text in a single heroic take of over two hours on Friday morning…

I’m really, really pleased with the result and very grateful to have had two such fantastic collaborators. And of course, none of it would have been possible without the generosity and support of the EMPAC team. Curator Kathleen Forde has been a longstanding supporter of my work and I’m looking forward to working with her on a show of my work next year. And Ian Hamelin and the rest of the technical staff at EMPAC are doing amazing work in demanding circumstances.

On to editing now – a version of The Flitter will be shown at Sketch in London in July. More soon…

Filming upstate (again)

I’m headed back to EMPAC this week to film a monologue with Carl Hancock-Rux. It’s a three hour monologue entitled ‘The Flitter’ based on an automated remix of part of my book Fair Use (notes from spam) – specifically the section called ‘The Wire’.

It’ll be showing as part of my show there next year and possibly as part of my show at Sketch in London in July this year.